As a learning and teaching support staff member, I’m in the business of suggesting new ways to do things. In every suggestion, I’m very conscious of the value and economy that such changes need to provide to make them worth any time investment.

One of the points of friction that I come up against is my internal perception that teachers might not want to try a new practice because it attends to something that is actually the students responsibility. Conversely, teaching staff may feel anxiety about what they could/should be doing for students to get the most out of their learning experience. I feel like these two things can be tied together with the phrase:

You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink.

Classic proverb

So, while you may have invested energy in providing something that you believe someone else needs, they may not absorb it because it requires considerable investment on their part. There is something, however, about this phrase that has always rubbed me the wrong way. We are taught in the design field that ‘it is never the user’s fault’. As a designer you can’t write off poor use of something you have created as being due to the user’s lack of appropriate action. You need to take wider user requirements into context as best we can when crafting a solution.

But then there is the teaching part of me that prepares and runs classes where students don’t do the readings, remain silent or ask questions that are already explained in the unit outline. I mean, like, come on. It’s easy to feel frustrated and disheartened, and increasingly so in the cameras-off world of online learning where it is difficult to see whether what you do is having impact.

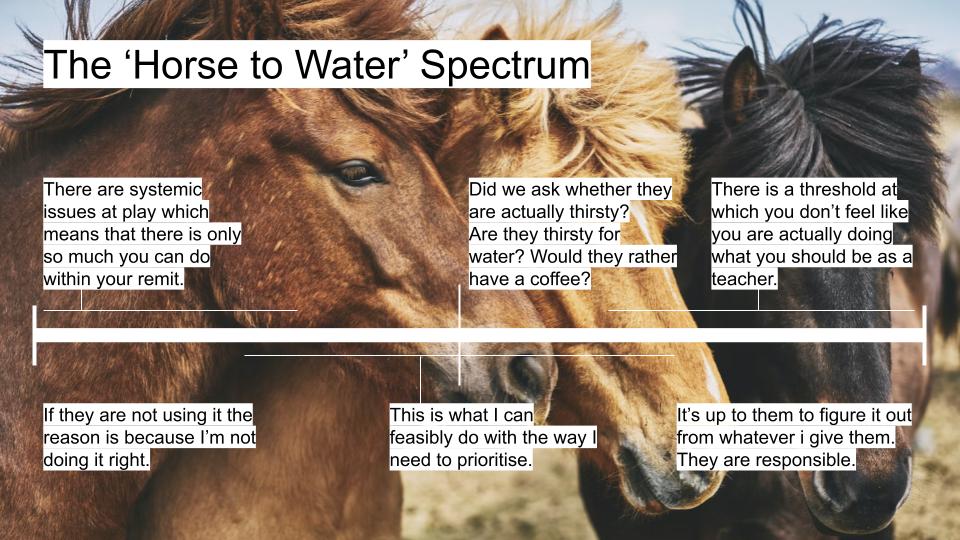

The ‘Horse to Water’ Spectrum

To visualise and communicate these ideas, I created the ‘Horse to Water’ Spectrum. Ultimately, mapping things out this way helped me realise some key things that provide greater clarity and help me work with, rather than against this problem space.

- On the right, we have the thought process that places the emphasis on student responsibility. If learners want to be part of this discipline, it’s hard, so they have to work to get there. I’d argue that this is built around ‘can’t or don’t want to’ rather than it being a fair expectation to put on students.

- In the middle are comments in relation to whether we are actually user-focused in tracking needs: are we asking the question of what they want, and are we perceiving the situation from their point of view?

- On the left-hand side are the thought process that comes from the desire to take personal responsibility for the entirety of the situation.

In laying things out this way, the key part for me was the realisation and acknowledgement of systemic issues and the part they play in the teacher/student experience. There are inevitably underlying systemic issues that any one individual may not be able to wholly change through their actions. For example, students may prefer to leave their zoom cameras off to have anonymity, or external priorities may limit the energy they have available for this part of their life. While the ultimate issue might not be within the scope of your learning interaction, having awareness and knowing how to influence change in small ways is more effective and rewarding than writing off the issue as a lack of student interest.

Overlaying all of this is capacity to prioritise. One’s own capacity to prioritise is always going to be in flux so this is probably where we would slide the most up and down the spectrum as we work through the different rhythms of a year and a career.

Horses for courses: finding your balance

While visualising the problem space doesn’t fundamentally help to fix the problem (sorry), it does help to alleviate some of the dirty discomfort of grappling with this as part of teaching experience. Points of friction will remain, but you are likely to understand them better and hopefully come to peace with them.

- If you have been pushed towards the right, your capacity to prioritise is probably the issue, so avoid writing off the issue as a student’s lack of interest in being responsible. Perhaps reconsider if there are any priorities that you can rearrange.

- If you are falling off to the left of the spectrum, remember that there are things that will always be beyond your control. Perhaps refocus on what you can control and work from there.

Existing in this system will always be an experience that challenges everyone. But we are all in it, working to do what we can with what we have available, and supporting each other to move things forward collectively.